Chris Lintott, Zooniverse, Oxford University

I think I’m here because we’ve run 44 Zooniverse projects, so you’d think I’d have some sense of what best practice is, but the truth is we are still in a phase where I can point you at stuff that doesn’t work and tell you what we are trying to do to fix that. We are not at a point where I can tell you how to build your definitive crowdsourcing project, which is fine, and exciting.

But there are some things in common across all 44 projects, so let’s see what we can get out of figuring out what’s in common. The first thing in common is that every project we’ve ever launched has run in two phases. There’s an enormous spike of excitement in interest and effort at the beginning, and then that drops back down and we have a long-term, stable set of volunteers that carry on. People come and go, but there are these two distinct phases.

So the first best practice is an obvious one, which is that you have got to design for both of these phases. That means you need a system that scales, that can stand up to the traffic at the beginning, but you also need something that is going to engage people for the long term. If the cardinal rule of crowdsourcing is not to waste anyone’s time, you need to be doing that when you’re busy and when things are quiet as well.

It’s worth thinking about the fact that the audience changes over time as well. At the beginning, literally no one is invested in your project. I know there are communities we think we are targeting with these projects. We thought we were targeting our first project, Galaxy Zoo, at amateur astronomers. But that kind of astronomy is different from an academic understanding of astrophysics, and so even amateur astronomers coming into Galaxy Zoo are neutral when they start regarding whether they care about this project. So you need to be able to give experience to people who haven’t yet decided whether they want to learn this stuff. I think we often lose sight of that. We need to make sure that we convince the people who are coming in before we do anything else.

That is really difficult because those of us in galleries and archives and libraries and museums sit in a reserved and specialized space. There is this concept I fell in love with from the museum world in the museum literature called “threshold fear,” which is the idea that you don’t go into a gallery unless you think you can get something out of looking at a painting. No matter what that gallery does inside its building to broaden its audience or to provide engagement, it won’t work unless you can get people up the steps.

And we have that in our projects. People browse onto our Zooniverse projects and as soon as they realize that something is real they have a visceral reaction to the fact that they are doing science, which they were terrible at in school. My guess is that this applies as much to the humanities as it does to the sciences because the kind of reading that you’re asking people to do or the kind of engagement that you’re asking people to have with the text is not natural to people, and it is something they haven’t grown up thinking of themselves as being able to do.

Dealing with threshold fear is important, and you have these two kinds of people. You have the dabblers, where you have to overcome that fear, and the people who are on board and committed to the subject. Both of those need to have a transformative experience. If you don’t have a long tail, if you don’t have these people who are going to stick around for months and work for the bulk of our effort, you need something that is going to transform people, the cautious dabblers who haven’t gone over that threshold yet, into committed people. And I think we know what that is.

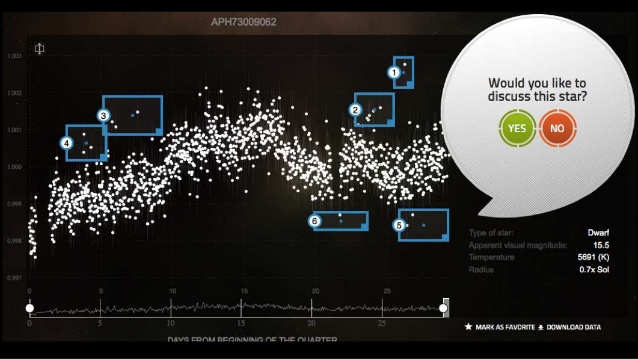

My second best practice is that what you do is give people a real experience that they believe in. That means convincing them that they’re going to do something useful. That they have done something useful is better. It’s much better to turn around and say, “Look, you did this and 37 other people agree with you.” Or, “You transcribed this text and now I know this.” It is showing both the large-scale results—people like you have helped us discover planets or find text—but also, “You mentioned this place in this text; there are 33 other people who have mentioned that place and look, here is how your point connects to theirs.” It is critical in transforming people from dabblers to committed volunteers.

I think that means that you end up building in two modes as well. You build a microtask that is immediately convincing and easy to grasp, and then you allow free exploration and discussion. You need both. I don’t think you can build a project that is just being done with things like comments on Flickr Commons. It’s not good enough to just say to people, “Come engage with our collection,” because they don’t believe that they can.

I have this hatred of the fashion in museums and galleries where, when you get to the end of an exhibition which has been beautifully curated, there are little bits of paper with the question, “What did you think?” And you pin it up and in some way you are supposed to engage with the process of curation. That feels like tokenism, and we keep building (at Zooniverse as well as everywhere else) the digital versions of that in which we say to people, “No, your comment is fine, do anything with it.” We need to do better than that. We need the microtask to convince and then you need the discussion and exploration.

That leads to my third and final best practice, which is that I don’t think we should be planning for our platforms and our projects to convince people of content. People shouldn’t go to Galaxy Zoo to learn about galaxies, they shouldn’t go to Operation War Diary to learn about the First World War. On those sites people are constantly engaged in learning as they go from a simple interaction to more complex interactions. They are learning how to use your features, how to use your discussion forum, how the community behaves, how to deal with the results that you’re giving them, how to interpret what they’re seeing.

What these projects do, the good ones, is they act as engines of motivation. We can show you that good projects convince people to go out and learn more elsewhere, to act much more like the engaged researchers that we want them to become. So you should not try to provide the platform for the full-scale engaged research experience. What we need is a tight, focused, believable, real, authentic experience that inspires people to go out and explore for themselves.

This presentation was a part of the workshop Engaging the Public: Best Practices for Crowdsourcing Across the Disciplines. See the full report here.

![[Video] Afrocrowd Works With Libraries and Museums to Improve Representation on Wikipedia](https://www.crowdconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2015-11-23-at-4.04.07-PM-500x383.png)

![[Video] Cooper Hewitt Part 2: Building a More Participatory Museum](https://www.crowdconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/21900187798_0a03dfec0a_k-500x383.jpg)

![[Video] Cooper Hewitt’s Micah Walter on Museums and #Opendata](https://www.crowdconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2015-11-10-at-2.25.30-PM-500x383.png)